The finest writers on art, at least in the English language, are Peter Schjeldahl and Waldemar Januszczak. And they straddle the Atlantic like two colossal light houses, the former from somewhere in Williamsburg where he files his celestial copy for the New Yorker, the latter from his muse in Chelsea where he writes a weekly column for the Culture section of the Sunday Times.

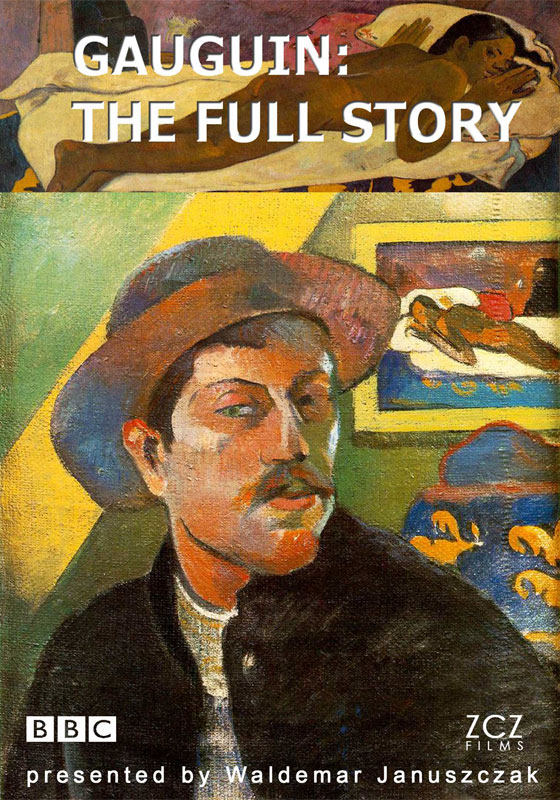

Januszczak has gone on to forge an almost flawless career as a documentary film and series maker where he focuses principally on late 19th century Paris. But he’s equally adept and comfortable on the Renaissance and everything in between. All of those movements that led from there to the birth of Modernism as it burst forth from Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

He is both deeply knowledgeable and consistently illuminating on everything from Picasso – on whom he teamed up with the peerless john Richardson — Gauguin, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, to the Baroque, sculpture and the birth of Impressionism, reviewed by me earlier here. But that ‘flawless’ is stained by that ‘almost’ courtesy of an albeit understandable fixation with the Sistine Chapel.

In 2011, he made his one and only dud, The Michelangelo Code: Secrets of the Sistine Chapel, which was recently screened again on the excellent Sky Arts. All of its parts are as engaging and enlightening as you’d have hoped and expected. All of that research into the Medici popes, the Franciscans and his meticulous reading of the bible and the scriptures was well worth the considerable effort it obviously cost him.

But none of it adds up to anything. There’s no there, there. He plainly sees some sort of connection between the Branch Davidians and that madness at Waco, Texas, and the chapel’s ceiling. But if anyone can tell me after watching it what that connection is, I’ll send you on a bar of chocolate and a can of fizzy pop.

He’s wonderful company and a glorious guide, and I am more than happy to have sat through the thing for the second time. But for the life of me, I’ve still no idea what any of it was actually about.

If you’re unfamiliar with Januszczak, then you should search out some of his articles, any of them. His criticism is absolutely bullet proof. And if you can, watch any of his documentaries. But you should probably treat The Michelangelo Code as something of a bonus track, a deleted scene. Strictly for aficionados only.

You can see the tailer for the Michelangelo Code here.

You can sign up for a subscription right, and I shall keep you posted every month on All the very Best and Worst in film, television and music!