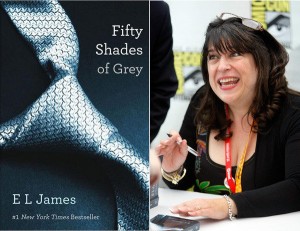

How sweet and honourable it is to live in this age of equality. A lot of snide remarks have been made about the quality of the prose employed in the 50 Shades series. And most of those have, surprise surprise, been proffered by men.

How sweet and honourable it is to live in this age of equality. A lot of snide remarks have been made about the quality of the prose employed in the 50 Shades series. And most of those have, surprise surprise, been proffered by men.

The world of literature has long been an enclave patrolled by men. What are they afraid of that they should so assiduously deny women entry there? Why shouldn’t they too sup with them there at the high table?

I congratulate E L James for taking one of the last bastions of male chauvinism and demanding that women be treated as equals there. And so, to that long and illustrious list of arenas where already this is true, we can now add the category of Carefully Marketed Airport Novel.

50 Shades is, impressively, every bit as resplendently unreadable as anything by Dan Brown. Each sentence seems to exist in a vacuum, related but peripherally to anything that came before or will follow after. Rather like the one I began this piece with above.

It’s as if a Martian were given the task of writing a book for humans, but instead of being allowed to visit Earth or in any way research what life on this planet consists of, all they were allowed to use as their basis for writing it was, well, a Dan Brown book.

Its plotting is as leaden as Jeffrey Archer’s, its prose as painful as John Grisham’s would later become, and it’s as cynically manufactured as anything produced by the conglomerate that is James Patterson.

Not only that, but it’s all of that all at once. E L James has managed to take all the most offensive traits from the most egregious male reprobates and fuse them all together in one fetid, faecal franchise.

Not only that, but it’s all of that all at once. E L James has managed to take all the most offensive traits from the most egregious male reprobates and fuse them all together in one fetid, faecal franchise.

Well I say, bravo. Here’s one more realm where women have now managed to sink every bit as low as their male counterparts.

They can now triumphantly litter their work-based banter with un-necessary expletives as thoughtlessly as any of their male colleagues. They proudly drown their weekends in an oblivion of alcohol, and are as comfortable urinating in public and caking the streets in vomit as they stagger home afterwards as the best of us.

And at long last, to tag rugby and Olympic boxing, they can add the producing of the most cynically conceived and ineptly written sub-soft porn. I hesitate to call it excrementally bad, as that at least suggests rejuvenation in the form of manure.

So congratulations. All we have to do now is to somehow get you girls in to the upper tiers of Wall Street and your journey will be complete. Well done. And welcome to the club.

Sign up for a subscription right or below and I shall keep you posted every week with All the Very Best and Worst in Film, Television and Music.