To their detractors, Led Zeppelin were far too commercially successful to be taken seriously as artists, and all too quickly succumbed to what then become a clichéd descent into a hedonistic hell of their own making, with the inevitably tragic result.

What this exhilarating documentary feature shows is that they’re far better understood as the spiritual forebears of Radiohead. A band of, in this case, four incredibly driven musical mavens hell bent on pursuing a very particular musical direction, who, inexplicably, wake up one morning to discover they’ve conquered the world, notwithstanding the singularity of that musical vision.

One of the reasons the documentary works so well is that, having shunned all and any publicity for their entire careers, especially documentaries like these, now that they’ve all agreed to finally participate in one, they are each uncommonly candid and open.

And they are ‘all’ here, as the three surviving members are accompanied by the voice of drummer John Bonham, thanks to a recently unearthed interview that Bonham gave before his death in 1980.

The reason these hitherto recluses have suddenly opened up so casually is the mutual respect that they and the film makers enjoy. And the reason for that is American Epic, which was the project that film makers Bernard MacMahon and Allison McGourty made before this one.

American Epic, which I reviewed earlier here, is a 3 part documentary that charts the birth of recorded music in America in the 1920s, and the musical genres that that gave birth to; the blues, country, bluegrass, RnB, rock ‘n’ roll, rap, hip hop and all manner of pop.

The argument this film makes, entirely convincingly, is the Led Zeppelin are the missing link that connects everything that came before 1969, and everything that followed, after 1970.

As much as anything else, this is cultural history rather than mere music history, in much the same way that Peter Garalnick’s towering Sweet Soul Music is as much about race and the America of the 1950s and ‘60s, as it is about Sam Cooke and James Brown.

So what we get for most of the first hour is a history of 1960s London, and the different paths that the four men take before finally forming the band.

There’s Jimmy Page, becoming one of the most in-demand session guitarists, and then producers in town, working with everyone from The Kinks and The Who to The Rolling Stones and Van Morrison.

While Bassist, and then arranger, John Paul Jones was similarly recording with all of the above, which is how they meet. While also arranging for the likes of Françoise Hardy, Shirley Bassey, Dusty Springfield and the Walker Brothers.

Eventually, in 1968, Page teams up with Jones to form a band, and, somehow, they enlist the talents of the force of nature that is Robert Plant, and his close friend and collaborator, drummer John Bonham.

In those days, the genial Plant was repelled from conventional society and mainstream culture in much the same way that electrons are in perpetual flight from the protons they orbit. Remarkably, the second he and the other three start playing together, everything fits into place, and sparks explode spectacularly into the ether.

When the film finally gives us a taste of the actual music, its sound is significantly richer from having been posited in the midst of the cultural and musical landscape that it sprang from.

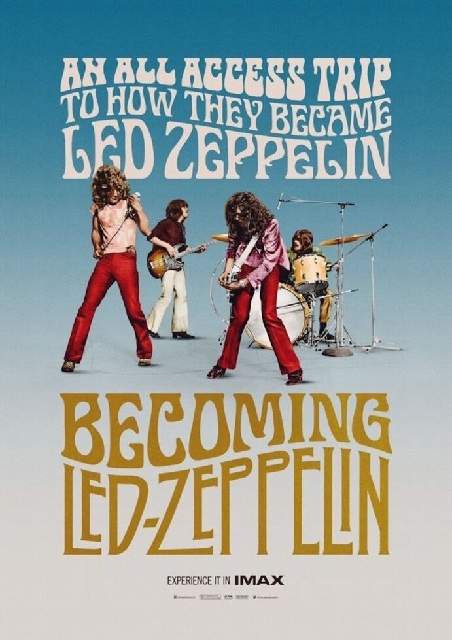

Different in size and scope to American Epic, Becoming Led Zeppelin is every bit as impressive, and makes for absolutely mandatory viewing. And should, if possible, be seen in a cinema.

And I defy you to resist immediately going in search of, at the very least, those first two albums the second you exit the cinema.

Watch the trailer for Becoming Led Zeppelin here:

Sign up for a subscription right or below, and I shall keep you posted every month on All the very best and worst in film, television and music!