Women Without Men sounds like it could be one of those dull, educational chores. In fact, it’s a sumptuous, richly evocative film that calls to mind the heady days of Italian cinema in the1960s and early 70s.

Think late Visconti, De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi Continis (reviewed earlier here) and the Taviani brothers. What if Bertolucci had ever managed to use his technical bravura to actually say something.

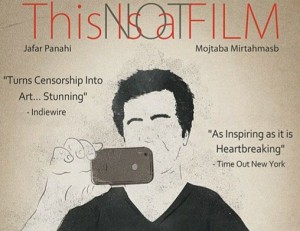

Shirin Neshat, whose first film this is, has said that she was influenced by Kiarostami when she decided to make the move from conceptual art into the world of feature films. But she is very much part of that new wave of Iranian film makers of Ashgar Farhadi, who made A Separation and About Elly (reviewed here and here), and poor Jafar Panahi, (reviewed here), who, outrageously, remains under house arrest in Iran.

Interestingly and unlike them, she is looking at Iran from the outside, having lived most of her life as an exile in the US.

Neshat has taken Shahrnush Parisipur’s famous novella, which charts the lives of four women, and has posited their stories against the backdrop of the events of 1953. It was then that the British and the US joined forces to overthrow the democratically elected government of Mosaddegh, and supplant him with a military dictatorship under the Shah, so the British could maintain their control of Iran’s oil supply.

Inevitably, indeed necessarily, revolution followed 25 years later. Immediately after which, the same crowd armed and funded Iraq in its war against Iran. And then they invaded Iraq, and then Afganistan, again, over yet more oil. And on it goes ad, patently, infinitum. Little wonder then that Iran looks at the West with such jaundiced eyes.

All of which could have resulted in a painfully dull film, part historical lecture, part feminist tract. But what Neshat has made instead is a marriage of magic realism and exquisite, formal precision. The result is ravishingly beautiful and quietly moving. Four female archetypes set against the backdrop of political turmoil, in the face of which, resistance appears futile. And yet, resist they must.

It won the Silver Lion at Venice in 2009 – in fairness, the Golden Lion went to the brilliant Lebanon. You should see them both, and you can see the trailer for Women Without Men here.

Sign up for a subscription right or below, and I shall keep you posted every week on All the Very Best and Worst in Film, Television and Music!